What have we here? Colonial destruction and looting

This is the other side of the violence in Palestine and Lebanon—an assault on history and identity—that we have not yet started talking about.

My son Deniz and I climbed the stairs on the left side of the Great Court and stepped into Room 35.

There’s something arresting about seeing them all together at once, side by side in a softly lit room. It feels as though you’ve stumbled into a hidden tableau—a secret desire, a veiled performance, a buried triumph, or an obscured carnage.

Something not far removed from a crime scene. And you, standing there, feel as though you’re on the verge of unravelling it. The room is filled with clues—enough to churn your stomach.

The space was packed. Each display cabinet was surrounded by at least five people, tightly pressed together, their heads bent to read the notes accompanying the objects.

One label posed a provocative question: ‘It is interesting that this chapter doesn’t crop up much in popular history. Which history is more important? Is that this monarch was a Catholic or a Protestant? Or that this monarch kick-started something truly horrendous? Which history we remember depends on what has been made visible for you.’

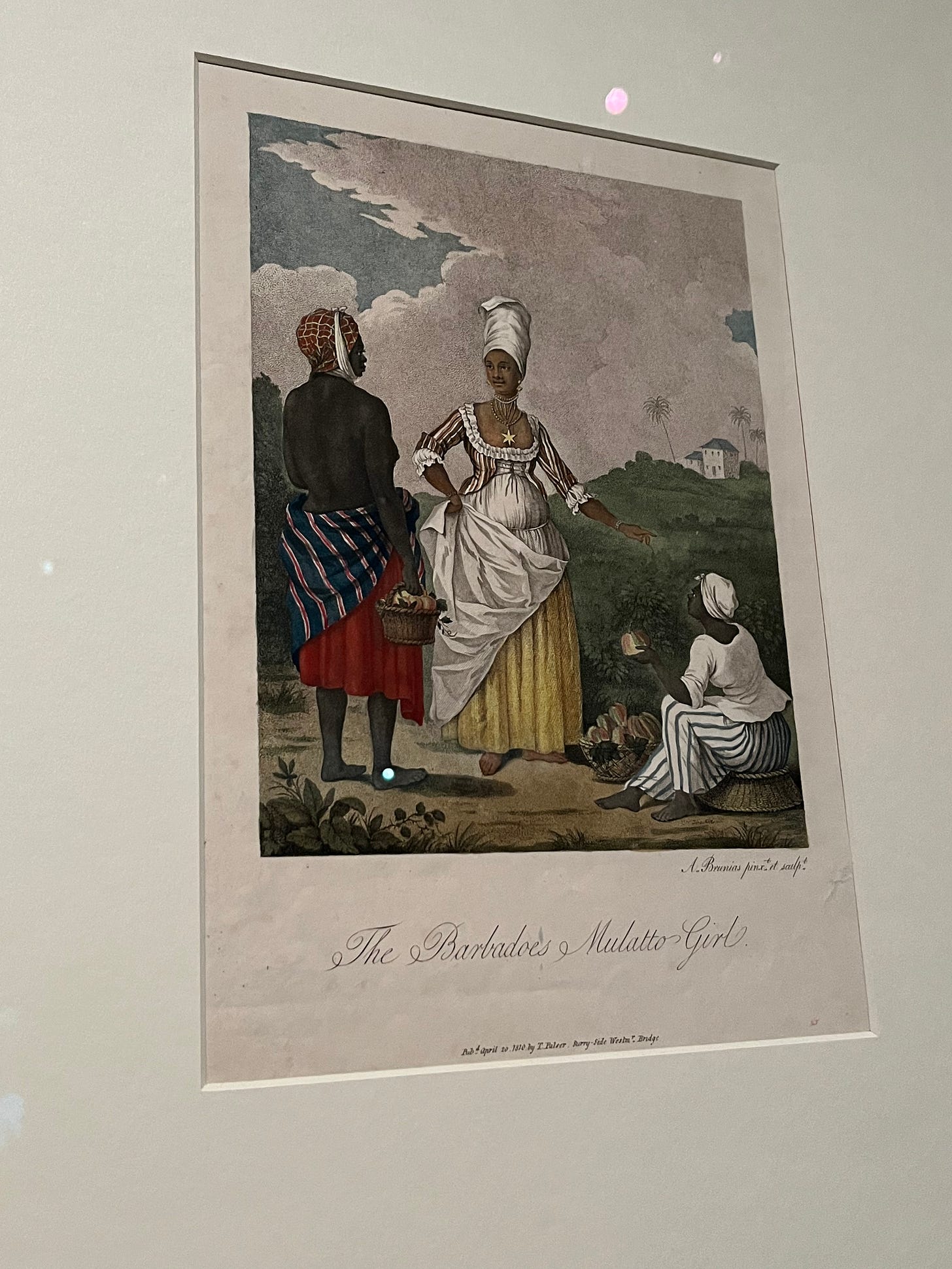

Another label delved into the interplay of color and class in a British colony: ‘The Caribbean has been described as a pigmentocracy – the lighter your skin, the higher up the tree you can go. But it’s more complex than that – class comes into it; religion comes into it.’

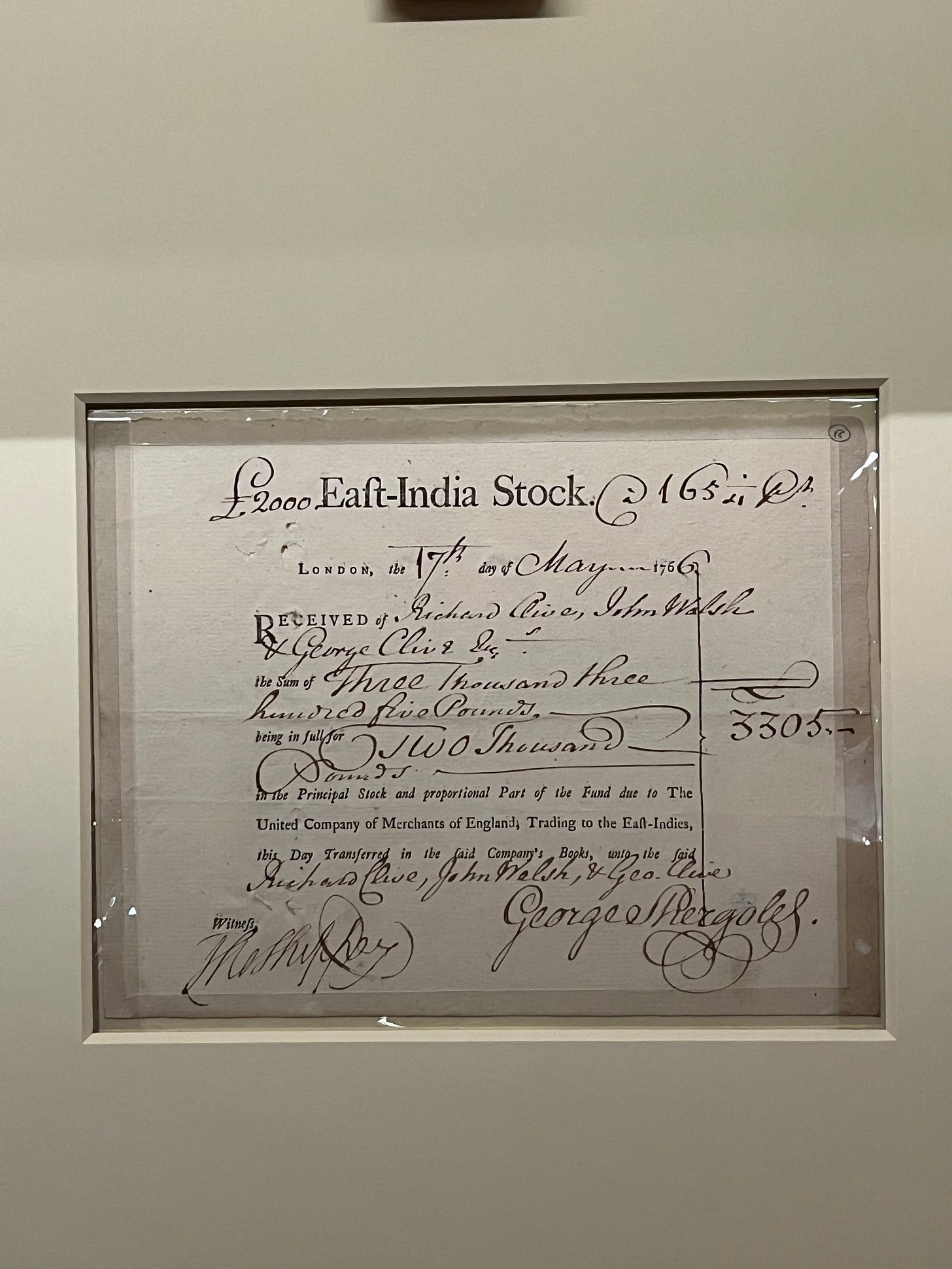

A third drew a striking contemporary parallel: ‘The East India Company functioned on a level that no company has reached today. This was a company run by a board of directors and really quite few employees, and it had an army that was bigger than the British army. It is as if Amazon had their army today.’

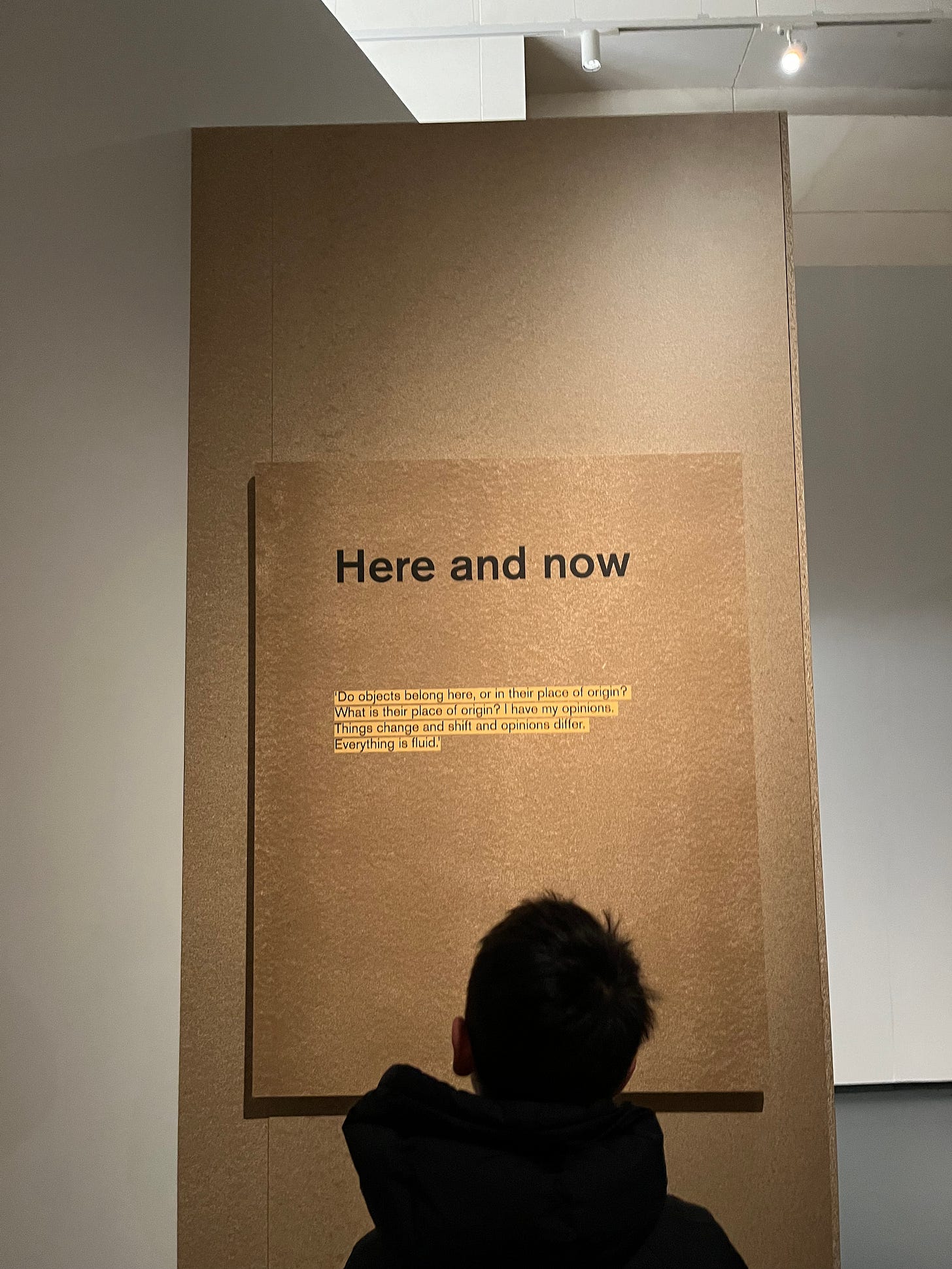

We are standing in What Have We Here?, an exhibition at the British Museum co-curated by artist Hew Locke.

The British Museum, established in 1753 as the world’s first public museum, embodies both the heights of human creativity and the shadows of imperial ambition. Its founding benefactor, Sir Hans Sloane, amassed a collection of over 71,000 objects through networks entrenched in British imperialism. His acquisitions were largely financed by wealth derived from enslaved labor on Jamaican sugar plantations, through his wife Elizabeth’s inheritance and his own royal appointments as a physician to British monarchs.

This imperial inheritance serves as the foundation for contemporary artist Hew Locke’s groundbreaking exhibition. Born in Edinburgh in 1959 to British painter Leila Locke and Guyanese sculptor Donald Locke, Hew Locke straddles multiple cultural worlds, lending him a distinctive perspective. Drawing on decades of engagement with the Museum’s collections, Locke has crafted its first artist co-curated exhibition to critically interrogate the institution’s history—challenging notions of ownership, purpose, and the provenance of its treasures.

In this exhibition, Locke unpacks the entangled narratives of power, sovereignty, and commerce. His evocative use of tulle-draped boats captures both the spirit of exploration and the anguish of forced migration, while raising urgent questions about how cultural artifacts are acquired and displayed. This critique resonates with ongoing debates over museum collections, many of which were appropriated during colonial conflicts before international laws against cultural looting came into effect in the mid-20th century. The British Museum thus emerges not merely as a repository of global heritage but as a reflection of Britain’s colonial obsession with collecting, classifying, and asserting control.

In every glass window, in each object looted from a colony, I thought about artefacts taken from Egypt, Greece, and Turkey.

We know that Greece has long pressed for the return of the Parthenon Marbles, taken in the 19th century, while Nigeria has sought the Benin Bronzes, looted during the 1897 invasion of Benin City. Egypt demands the Rosetta Stone, a cornerstone of its cultural identity seized in 1801, and Ethiopia has called for treasures taken after the 1868 Battle of Maqdala. Easter Island has appealed for the repatriation of the Hoa Hakananai’a statue, removed the same year. In 2023, China renewed calls for the return of numerous relics, citing improper acquisitions. Turkey has pursued artifacts such as the Samsat Stele and Lion of Knidos, alongside broader efforts to recover Anatolian and Ottoman-era heritage lost to foreign collections.

The debate over contested artifacts goes far beyond museum collections—it is deeply entwined with the violence and erasure of cultural heritage in conflict zones. My thoughts turned to Iraq, where the U.S. invasion opened the door to widespread looting, and ISIS obliterated historic sites in acts of destruction that felt almost ritualistic. Then there is the ongoing devastation in Gaza, where mosques, churches, and archaeological sites have been reduced to rubble. Similarly, in Lebanon, Israeli strikes near Baalbek and Tyre have endangered and damaged monuments of immense historical significance. What have we here? A glaring manifestation of plunder and destruction, perpetuated by a contemporary colonial project.

This is the other side of the violence in Palestine and Lebanon—an assault on history and identity—that we have not yet started talking about.

Do visit What Have We Here? if you find yourself in London before 5 February.

A small ‘Victory’ for a Roman Emperor in Turkey

A few weeks ago, Tuna Şare Ağtürk, professor of classical art and archaeology at the University of Oxford, delivered a lecture on her renowned excavation in Çukurbağ, Kocaeli, in northwest Turkey. Her work unearthed the ancient Roman city of Nicomedia, the empire’s eastern capital under Emperor Diocletian in 286 AD. While describing the monumental imperial complex adorned with vividly painted marble reliefs depicting imperial figures and mythological scenes, Ağtürk shared a troubling story of smuggling.

"In 2017, I received a message from an Italian colleague who knew I was working on Nicomedia," she recounted. "They asked if a marble relief about to be auctioned might belong to our excavation. After examining the auction catalogue, I was certain it had been stolen from Kocaeli and contacted the Ministry of Culture."

The relief panel in question, depicting an emperor alongside the garland-bearing goddess Nike/Victoria, had been illegally removed during the 2009 rescue excavation. It first surfaced in 2013 at an auction held by the art dealer Gorny & Mosch in Munich, Germany, before being withdrawn—only to reappear in 2017 with a fabricated provenance claiming it had belonged to a private English collection since 1971. Listed for sale at 40,000 euros, its reemergence prompted Ağtürk and the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism to take swift action. The ensuing lawsuit stretched on for two years, but in 2019, the panel was finally returned to Turkey, first to the Anatolian Civilizations Museum in Ankara and later to the Kocaeli Archaeology Museum.

This hard-won return is a small but significant “victory” in the ongoing battle against the looting and destruction of cultural heritage—a struggle that spans centuries and continues unabated.

Do watch the movie La Chimera directed by Alice Rohrwacher, featuring Josh O'Connor as Arthur, a British archaeologist entangled in the illicit trade of Etruscan artifacts during the 1980s.

(Tuna Şare Ağtürk’s book on Nicomedia’s reliefs is here. For Turkish speakers, her popular art history class is here.)