Sharra’s Schedule: On Fidan’s Advice to Riyadh, Aboard Erdoğan’s Plane to Ankara

This week’s article has two parts. First, we’ll turn to the Syrian president’s visits to Riyadh and Ankara. Then, we’ll examine cultural hegemony and the AKP’s offensive against artists in Turkey.

Following the section on Syria’s interim president Al-Sharra’s first two foreign trips—first to Riyadh, then to Ankara—the next discussion shifts to a broader, more conceptual issue: cultural hegemony and the right-wing assault on artists, journalists, and academics. It runs a tad bit long, but skipping it would disappoint me :(

As you may recall, Syria’s interim president, Ahmad al-Sharra, held his first meeting with a foreign minister—not with an Arab counterpart, but with Turkey’s Hakan Fidan—shortly after he effectively assumed office in Damascus.

Before that meeting, a suit was sent to him from a well-known Turkish luxury brand. Shoes, too. Since then, al-Sharra has hosted a steady stream of high-level emissaries from around the world. But his first foreign visit had to be symbolic. The AKP—more precisely, Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan and spy chief İbrahim Kalın—advised him to follow the same script they had laid out for Egypt’s late Mohammed Morsi: start with Saudi Arabia.

Late Morsi’s first foreign visit as Egypt’s president had been to Riyadh in July 2012, where he had met King Abdullah to discuss economic cooperation and regional security. The trip was designed to calm Gulf fears—to reassure them that Egypt, under the Muslim Brotherhood, would not be a problem.

The case of Syria carries a similar dual objective: to appease Saudi concerns about an Islamist government in Syria undermining the legitimacy of their monarchies—potentially prompting efforts to destabilize al-Sharra’s rule—and to secure financial backing for Syria’s collapsing economy.

After he met with Mohammed bin Salman, al-Sharra, along with his wife Latifa [al-Daroubi] al-Sharra (making her first public appearance), traveled to Mecca to perform Umrah. He was even granted entry into the sacred inner sanctum—a privilege reserved for heads of state. The official readouts and the photo ops of the Riyadh trip signal that the meetings were positive.

In other words, al-Sharra’s first foreign visit to Riyadh was not just about Syria—it was also about Turkey. Ankara wants to avoid provoking the Gulf monarchies into believing that Turkey is positioning itself as the dominant force in post-Assad Syria, stepping into the vacuum left by Iran—a shift that could trigger Gulf pushback and put Israel on edge.

After Riyadh, al-Sharra and Foreign Minister Ahmad al-Shaibani—who studied in Istanbul and speaks fluent Turkish—boarded Erdoğan’s plane to Ankara. In Beştepe, Erdoğan’s presidential palace, discussions focused almost entirely on security. First issue: the de-facto autonomous administration of the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF).

By now, al-Sharra must have grasped Turkey’s red lines: No SDF military structure outside the regular chain of command—only full integration into the new Syrian army, no SDF-led Kurdish autonomy in northwest Syria. He’s been negotiating with Mazlum Abadi - the SDF leader- but hasn’t struck a deal—yet.

Second, a security pact that would allow Turkish forces to train the new Syrian army, soon expected to function as a unified force. The deal would also authorize the establishment of a Turkish-run military base in Syria.

According to Reuters’ sources—a Syrian security official, two foreign security sources based in Damascus, and a senior regional intelligence officer—the discussions remain confidential, as none of them were authorized to speak publicly about the meeting. This is the first time details of a strategic defense agreement under Syria’s new leadership—including plans for additional Turkish military bases—have surfaced.

The proposed agreement would allow Turkey to set up new air bases in Syria, use Syrian airspace for military operations, and take the lead in training the new Syrian army. The regional intelligence official, along with the Syrian security source and one of the Damascus-based foreign sources, indicated that negotiations include plans for two Turkish bases in Syria’s central desert region, known as the Badiyah. Potential locations? Tadmur military airfield in Homs province and the T4 military base, currently controlled by the Syrian army.

Conspicuously, this security deal would make Israel, positioned in Syria’s southern Quneitra province, uneasy. Since a Turkish base is, one way or another, also a NATO base, it would not be welcomed by Iran or Russia either.

Right-Wing Rage Against Artists, Journalists and Academics

As you might recall, Turkey’s leading artists have come under siege from all directions—targets of coordinated social media troll campaigns, state investigations, and even the looming threat of imprisonment.

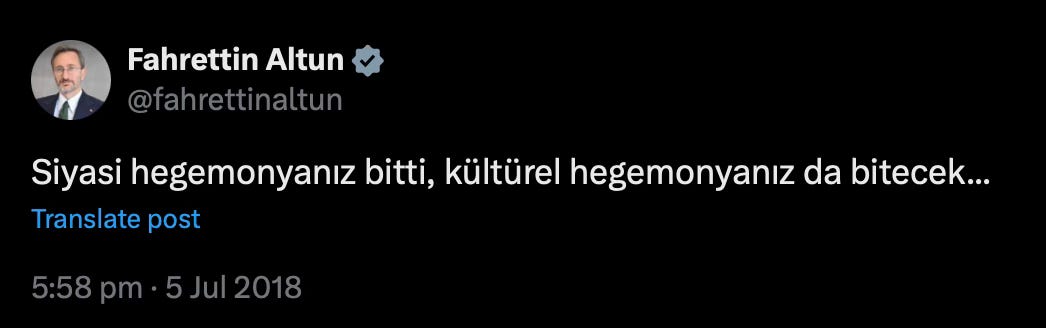

I had mentioned in last week’s letter my intention to explore the concept of cultural hegemony—something Erdoğan and the AKP have, since at least 2017, openly lamented failing to achieve. Erdoğan, predictably, frames the issue through the lens of gender ideology, accusing “the others” of imposing LGBTQ values, eroding the so-called “real people’s” traditional way of life, corrupting morality, and destabilizing the family structure. Textbook right-wing populism. Nothing surprising there. His communications advisor, however, has taken a different approach, articulating the argument in more Bourdieuian terms. In a 2018 tweet, he declared: “Your political hegemony has ended; your cultural hegemony will end as well.”

Will it?

There are layers to this. Erdoğan has every reason to be frustrated—despite two decades in power, his party has failed to generate the kind of cultural capital that could supplant the entrenched republican cultural codes that still define class status. But he also shouldn’t be too disheartened, because cultural production is not confined to the realm of aesthetics and the arts. And in other domains, the AKP has done just fine. Let’s take a closer look.

Erdogan is upset and rightly so. Power isn’t just about who controls wealth or wields political authority—it is embedded in culture, shaping what people see as natural and inevitable. Bourdieu calls this cultural capital—the tastes, knowledge, and habits that signal belonging and status.

Allahları var, they have tried—and are still trying—to weaponize nostalgia for a fabricated Islamic or Ottoman golden age, along with patriotism, to cultivate mass appeal. Over the years, they have attempted to flood the market with sentimental novels glorifying traditional family values and religious revivalist art meant to serve as vehicles for their conservative worldview. They sought to amplify these efforts through their newly acquired media empires. It failed. These cultural weapons fell flat on the battlefield because they were too parochial, too contrived, despite the grand claim that they were resurrecting authentic Turkish and Muslim cultural traditions.

But Erdoğan shouldn’t be too upset, because he has something far more consequential—control over the habitus, the very real arenas of struggle: education, media, and politics. These are the fields, as Bourdieu would put it, where power defines the rules, deciding whose voices matter and whose do not. And in Turkey, who owns these fields? Who holds the real pouvoir? After more than two decades of uninterrupted rule, the AKP has ‘almost’ full control over education, media, and politics.

Yes, the AKP’s attempt to engineer a more conservative generation did not fully succeed. In my view, it has failed. But that does not mean we should overlook a crucial shift: the increasing convergence in lifestyles and aspirations between Islamic and non-Islamic middle classes, both shaped by a neoliberal worldview. The AKP may not have won the culture war in the way it intended, but it has reshaped the battlefield.

When analyzing the AKP’s rule through a Gramscian lens, Prof. Cihan Tuğal of UC Berkeley has always been one of my key references. I reached out to him for his thoughts on recent developments, and I have to say—I’m pleased to see that Cihan Hocam shares my perspective. Succinct and sharp, as always:

I have generally avoided using the term "cultural hegemony" because, in my view, culture and politics are deeply intertwined in all aspects of life, making the distinction somewhat artificial. It is often said that the AKP has failed to establish cultural hegemony, but I find this framing misleading. It would be more precise to say that the party has failed to dominate highbrow cultural spheres—mainstream theater, for instance—simply because its ideological and institutional formation does not lend itself to such spaces.

In middlebrow culture, however, there is a clear effort. The television and film industry is part of this struggle—an arena the AKP could theoretically capture but has never fully controlled, which is precisely why the battle over it has become so intense.

But in popular culture, their hegemony is undeniable. The fact that nearly all arabesk singers, a significant number of pop stars, and even a few folk and so-called protest musicians openly align with Erdoğan is no small feat.

Another reason I avoid the term "cultural hegemony" is that I use "culture" beyond the artistic and aesthetic domains. Higher education, for instance, is at the very heart of cultural conflicts. Here, the AKP has not achieved full hegemony, and Boğaziçi University has become the ultimate symbol of this failure. I’ll speculate further: institutions like Boğaziçi can be encircled, eroded, and hollowed out, but the AKP lacks the capacity to build an equivalent alternative. The situation in television and film, however, is somewhat different.

Then there is grassroots education—the neighborhood-level training grounds. Qur’an courses, in my view, are one of the most crucial sites of hegemony, yet they are rarely discussed as part of the "cultural hegemony" debate, simply because they are associated with low cultural capital and are not perceived as “cultural” spaces in the traditional sense.

Finally, the boundaries between highbrow, middlebrow, and popular culture are far from clear-cut. Certain refined forms of arabesk contain highbrow elements, just as elite academic institutions harbour plenty of vulgarity—and, in some cases, which I would argue is not always a bad thing, an element of populism.’

[For Turkish readers here is Cihan Tugal’s article on academia and elitism.]

The hostility is global

It’s worth recognizing that hostility toward artists, intellectuals, and academics is not just a personal quirk of Erdoğan—it is a deliberate strategy, one shared by almost all right-wing, illiberal populists, whether in Latin America, Central and Southeast Europe, the Middle East, or, more recently, North America. In other words, it is not specific to his brand of Islamism. In this context, Islamism is just another right-wing ideology—not even as thick-centered as nationalism, morphologically speaking—but unmistakably right-wing.

Just look at what Trump’s vice president, Yale alumnus J.D. Vance, had said in his speech at the National Conservatism Conference in 2022: "Professors are the enemy" (quoting Nixon) and "We are giving our children to our enemies, and it’s time we stopped doing it." If I translated this into Turkish and showed it to my aunt, she’d be convinced it was Erdoğan. It could just as easily have been Orbán. Bolsonaro. Modi. Meloni. Sisi.

Right-wing populism feeds off anti-elitism and anti-intellectualism—it must challenge these institutions, portraying them as out-of-touch, corrupt, or subversive. The populist leader presents himself as the voice of the people, locked in a battle against an intellectual class that supposedly looks down on ordinary citizens and imposes its values through media, education, and the arts.

This isn’t just an impulsive backlash; it’s a calculated strategy. Right-wing movements know they must disrupt the dominant cultural hierarchy—the "fields," as Bourdieu would put it—to legitimize their own cultural production. Universities, seen as breeding grounds for liberal or progressive thought, become prime targets for defunding, censorship, and ideological restructuring. Bourdieu’s concept of symbolic violence is at play here: conservative and populist movements don’t just reject elite cultural spaces—they actively work to delegitimize and dismantle them. They resent these institutions because they control the narratives, histories, and knowledge systems that shape society’s understanding of itself. That is a direct challenge to their rule—or, more precisely, their hegemony.

And if you still haven’t noticed, journalists are enemy number one. The first and foremost target. Professors are dismissed as "indoctrinators," and artists as "degenerates." Journalists? "Terrorists," of course. Or "enemies of the people," surely.

This is not just propaganda; it is an attempt to construct a new symbolic order, one in which their worldview is not only politically dominant but culturally entrenched. And unfortunately, this is not just a localized trend—it is a global tide.

Such an insightful article, Ezgi. You may remember me? In spite of everything, we must not forget the FEAR factor. Fear is a prominent and defining factor of Turkish culture, politics and much of Turkish life.

I have (only) majored in Comparative Literature but I loved my Bourdieu seminars (comprehensible - not only Flaubert etc. - one of the 3-4 topics on my Master's examn was on Bourdieu's theories on religion) because they provided a massive treasure of insights (btw nowadays I would perhaps rather choose Political Science, Sociology and History than literature - I relish reading your work here - very interesting indeed) and I must say it literally made my "political" heart sing to read this acute analysis! Yes! Thank you very much not only for elaborating on your special field of expertise but also for outlining these subtle structures which are at play everywhere...

I still believe that calling this out - just to explain the forces at play here - gives so many people a clearer view (and maybe the incentive to take up their respective 'tools' to dismantle the dangerous nonsense which stands between healthy democracies and rogue players wanting to undermine every single empowering force for good and decent political work.