Sane-washing the Israeli officials

At the very least, we discovered that some people, more than others, are deemed to have a greater right to return to their land.

Last week went by with men in barbershops and coffee shops across the Middle East, and some of us elsewhere, tuned in for Hassan Nasrallah's - head of Hezbollah - speech in the aftermath of Israel’s attack on Lebanon by implanting tiny explosives into devices that operate via radio frequency such as pagers and walkie talkies. Is he going to declare all-out war against Israel? We tried and tried to read between the lines. But there were no lines, no in-betweens. Just Israel's impunity and bearded autocratic men responding to it - one way or the other. This is our new routine.

Another routine is the complete loss of sanity through the process of "sane-washing" insane political moves. As I learned from American writer Rebecca Solnit on Alan Rusbridger and Lionel Barber’s Media Confidential podcast, this term now refers to news outlets attempting to mold Trump’s incoherent ramblings - Solnit calls them word soups - into something resembling policy or a coherent statement when in reality, they’re simply gibberish. I believe a similar kind of sane-washing has been applied to Netanyahu and his far-right cabinet’s actions since last year. Euphemisms have been endlessly used and abused in this effort. I won’t delve into all of them—at least, not today.

However, I truly cannot fathom why news presenters fail to ask a simple, straightforward question when someone from the Israeli PR machine claims that Israel's recent offensive on Lebanon is about displaced Israelis from the north. It’s extraordinary that certain former and current Israeli officials, along with high-ranking government figures, can—with a straight face—insist that these displaced Israelis have a "right to return to their land" but cannot do so as long as Hezbollah continues firing rockets. ‘Returning to one’s land’ seems to be an entitlement reserved solely for Israelis.

As Israel wages war on Lebanon, officials maintain that "their war" is with Hezbollah, not the Lebanese people. Yet, by the third day, 492 people were killed - 35 of them children- and 1,024 injured. It was Lebanon's deadliest day since the 1990s. Israel isn’t shifting fronts; it's intensifying its daily ferocity. But also, Hezbollah is a much bigger and well-structured organisation than Hamas with 50,000 men in arms even during peace times. This number must have been doubled since last October.

This conflict teeters on the brink of a broader Middle Eastern war, but the madness behind it is seldom questioned, instead being sane-washed as a campaign for the "displaced people of Israel." At the very least, we’ve learned that some are more entitled than others to the so-called "right to return to their land."

In the coming days, we may witness Israel launching a ground invasion, knocking on Beirut’s door, with Hezbollah inevitably responding in one way or another. This is madness.

Saddam, the Kurds, and the rice producer of Louisiana

I had no intention of engaging with the people of Louisiana, but a twist of fate brought me there, revealing important historical lessons through two distinct incidents.

First: Year 1987-88. Saddam Hussein’s cousin, Ali Majid al-Tikriti—infamously known as Chemical Ali—led a genocidal campaign against the Iraqi Kurds, deploying chemical weapons. At the time, the U.S. maintained a cozy relationship with Saddam. Peter Galbraith, serving on the U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, traveled to Iraq and authored several reports on the Kurdish regions. His efforts played a key role in exposing Saddam’s systematic destruction of Kurdish villages and use of chemical weapons.

The Reagan Administration was briefed on the situation. A State Department cable on U.S.-Iraqi relations explicitly stated, "we have evidence of chemical weapons use against the Kurds since at least the Spring of 1987." Yet, in a telling turn of priorities, it continued, "human rights and chemical weapons use ASIDE (emphasis mine), in many respects our political and economic interests run parallel with those of Iraq."

Galbraith then did what any decent, responsible policymaker should: he drafted the "Prevention of Genocide Act of 1988," aiming to impose sweeping sanctions on Iraq in response to the chemical attacks on the Kurds. The Senate passed the bill unanimously. But this is when the Louisiana rice producers entered the fray. Galbraith's bill included a clause prohibiting the sale or transfer of any export items to Iraq. Agricultural exports to Iraq had surged in recent years, with nearly a quarter of Louisiana’s rice exports going there. If the bill passed, what would the rice producers do? The backlash was swift and fierce.

At that time, a staff member from Louisiana approached Galbraith, tears in his eyes, accusing him of committing "genocide" against the rice producers. On one pan of the scale were the teary-eyed rice producers in Louisiana and other stakeholders in the US; on the other, the bodies of Iraqi Kurds, covered in white dust from sarin and mustard gas. What do you think tipped the balance?

The genocide bill failed to become law - due to oppositsion from the Reagan administration, which deemed it ‘premature.’

Lesson: Politics is a vocation driven by power and interests, not values. It always has been, and it always will be. We shouldn’t be surprised by how the Biden Administration is handling the atrocities in Palestine—there’s nothing new in that.

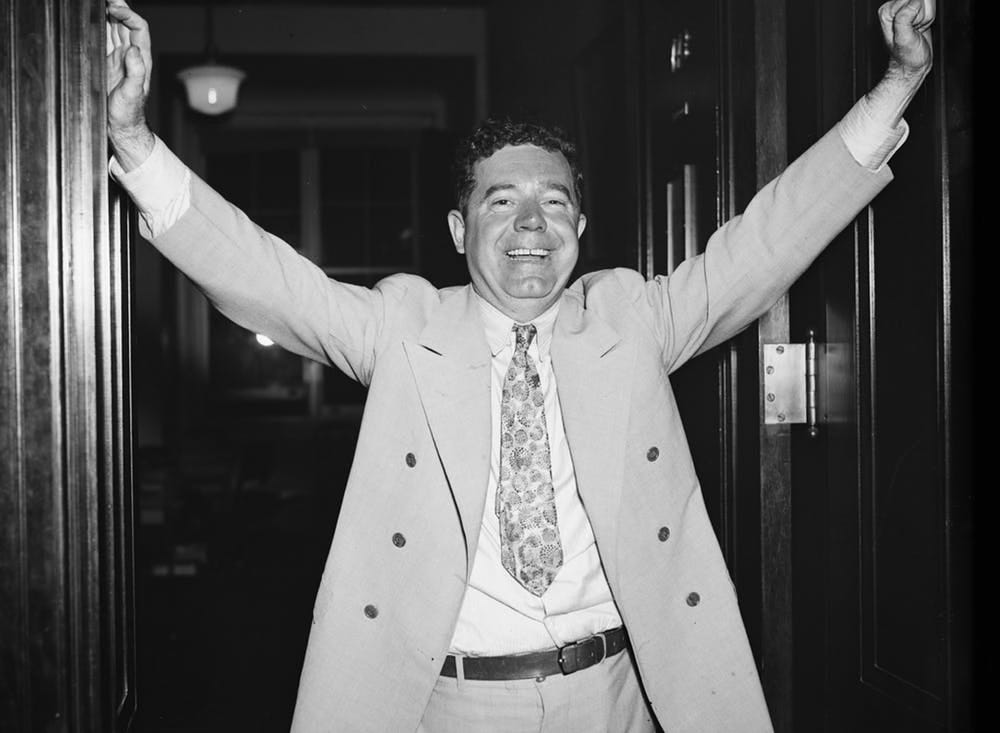

Second: After Donald Trump has vowed to slash hundreds of jobs across federal agencies should he return to office, some scholars and media pundits felt the urge to explain what state capture is. Anne Applebaum, whose book Autocracy Inc. was published recently, draws parallels between European autocrats—particularly in Poland, Hungary, and Turkey—and Louisiana's 40th governor, Huey Long, a populist with illiberal tendencies. In the Autocracy in America podcast by Applebaum and Peter Pomerantsev, they detail how a volatile and controversial politician systematically employed authoritarian tactics to dismantle checks and balances, ultimately taking control of the government apparatus in Louisiana. When I heard the steps that Long took to capture the judiciary, it sounded all too familiar to me: An Erdogan in Louisiana in the late 1920s.

Lesson: It reveals that autocratic leaders, no matter when or where they emerge, follow a familiar learning curve and playbook. Western institutions are not immune to such figures, nor do they hold up 'way better' than their Middle Eastern counterparts. This persistent belief is an Orientalist misstep that keeps resurfacing in discussions, and I’ve grown weary of it.