Foundations of ‘the first order’ in the modern Middle East

Rogan argues that the formation of the modern Middle East and the birth of ‘a new order’ can be traced back to the violent events of 1860.

As Israel invades southern Lebanon—a ‘limited military incursion’ it said, as it claimed nearly two decades ago—it bombs a crowded Palestinian refugee camp in Sidon.

Imagine being a Palestinian, fleeing the horrors of Gaza or the senseless, brutal killings in the West Bank, seeking refuge in Lebanon. You barely survive in a tent with your siblings, cousins, uncles, and aunts, only for another bomb to shatter your life—once again.

Now, Israel advances to the next phase of its war ‘against Hezbollah’— ‘We have no issue with the Lebanese’, it said, just as it had no issue with the Palestinians—flattening civilian neighbourhoods in the process.

Imagine being a Syrian, displaced, fleeing the nightmare that is your homeland—caught in the quagmire of civil war, where Assad, jihadist factions, and power-mad opportunists from Iran, Turkey, and Russia vie for control. You flee to Lebanon in search of respite.

In the Middle East, geography isn’t just destiny; it is a relentless torment, a hellish Groundhog Day.

This grim predicament prompts discussions of a change in the order of the Middle East. But what 'order' are we referring to? Or more precisely, whose order created the conditions that have left this region so saturated with turmoil?

According to the Oxford school, or more specifically the Albert Hourani-Eugene Rogan tradition, the history of the modern Middle East begins with an edict read in Istanbul in 1839, which launched a series of modernization reforms known as the Tanzimat by the Ottoman Empire. This decree altered the configuration of the societal dynamics within the Ottoman Empire, leading to several bloody upheavals across the vast region of Greater Syria in the mid-19th century.

The Tanzimat—literally meaning "reorganization"—marked the Ottoman Empire's effort to modernize its bureaucracy, judiciary, and military, while reshaping its millet system to fit the model of a modern state. But why did the Ottomans embark on this sweeping modernization? In the wake of the Balkan trauma, were they attempting to stave off European interference and protect the social fabric and economy of their prized Bilad al-Sham provinces? This is one part of the inquiry. The other part should deal with the consequences of this reorganization on the relationship between state and society.

In the aftermath of the Tanzimat decree, a major sectarian-tinged violent event took place in Aleppo in October 1850. Muslims from the eastern quarter of the city attacked the Uniate Catholic communities of Jadayda. A rumor that the Ottoman government was about to impose conscription on all Muslim men sparked protests that quickly escalated into violence against the Christian neighborhood.

The introduction of blanket conscription diminished the status of the janissaries, who were predominantly based in the eastern suburbs and had once been the most feared and powerful element of the Ottoman military. The shift in power wasn’t just institutional; communal bonds were also strained. Non-elite Muslims, feeling increasingly marginalized, viewed the Tanzimat reforms as un-Islamic. Meanwhile, the once-prosperous Christians, who had previously sought alliances with their Muslim neighbors, began to look toward European powers instead. The rioting, though limited to affluent Christian suburbs and trade hubs, was symptomatic of deeper tensions.

Order was eventually restored, but similar violence erupted in nearby provinces the following decade—first in Mount Lebanon, then in Damascus.

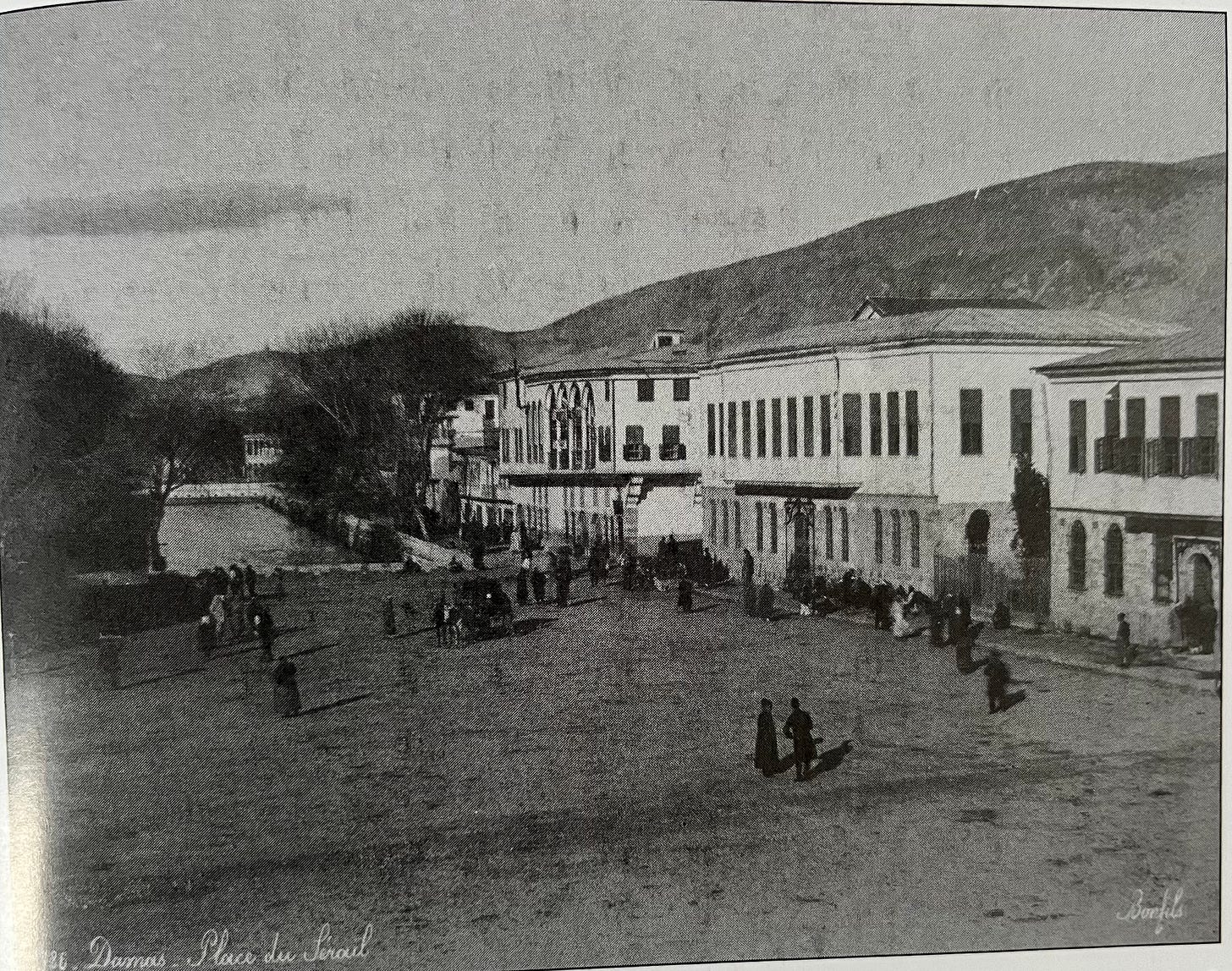

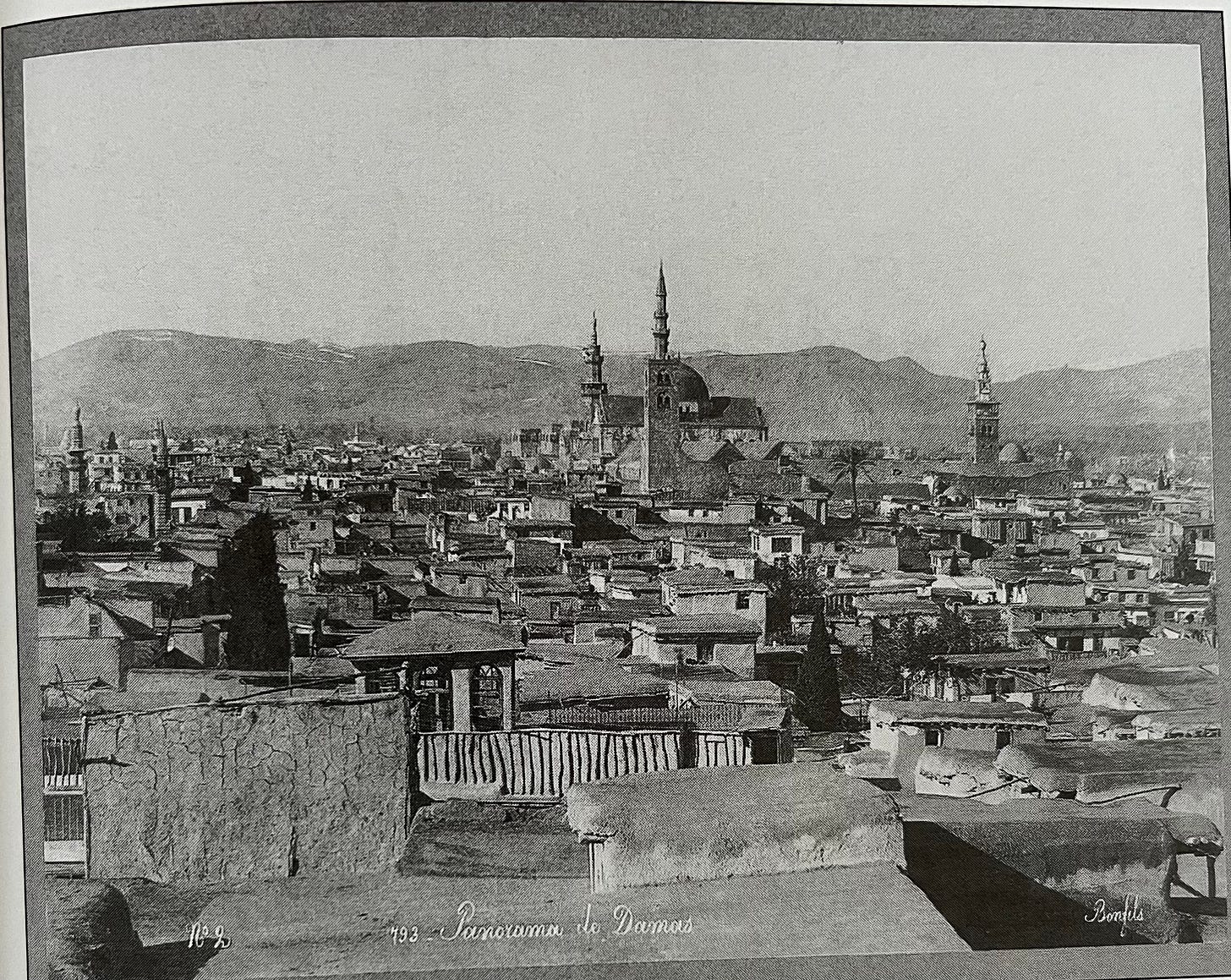

In mid-June 1860, clashes broke out between the Druze and Maronites of Mount Lebanon, which ignited further violence in Damascus. Hundreds of thousands were killed or wounded. In the chaos, Muslim Damascenes attacked Christians, slaughtering them and pillaging their homes.

Two of the most commercially and socially vibrant provinces of the Ottoman Empire had descended into acrimony and bloodshed.

But why? Was this region always destined for such turmoil? Or were there other factors—many still at play—that fuel these societal tensions?

The answer lies in Eugene Rogan’s beautifully written book, The Damascus Events, with its captivating dramatis personae. Rogan transports us to the Tanzimat era in Syria and Lebanon during the mid-19th century. He skillfully weaves together archival material - the vivid reports and letters of Mikhail Mishaqa, the U.S. vice-consul to Damascus at the time.

Rogan argues that the formation of the modern Middle East and the birth of ‘a new order’ can be traced back to the violent events of 1860:

‘For Syria and Lebanon two of the keystone states of the modern Middle East, 1860 Events were a defining moment: a definitive break with the old Ottoman order and a violent entry into the modern age. Before 1860, the Ottomans left Syria and Lebanon to their own devices, with local institutions and factions competing with Ottoman governors for control. After 1860, both Damascus and Mount Lebanon came under a far more centralised government, rolled through a bureaucratic state with elected officials, anticipating the statecraft of the twentieth century. Syrians and Lebanese trace the beginning of their fateful relationship with France, their twentieth century imperial power, to the 1860 Events. Moreover, the Lebanese link the origins of their complex sectarian form of government to the 1860 Events and trace every subsequent civil war back to the ‘original sin’ of 1860. This is as true for the brief Lebanese civil war of 1958 as it is for the fifteen-year conflict spanning 1975-1960. In many ways, the modern history of Syria and Lebanon begins in 1860.’

Historians resist using history as a blueprint for addressing today’s challenges, as that is not the purpose of historical inquiry—and simply put, it doesn’t work. However, history undeniably deepens our understanding and allows us to view the world from new perspectives. As Rogan aptly states, ‘History does not provide a road map for solving contemporary issues, but it does demonstrate what is possible.’

Now is the perfect time to read this book, written by a brilliant historian and true admirer of Arab culture and peoples. Eugene Rogan’s The Damascus Events: The 1860 Massacre and the Making of the Modern Middle East is now available.