Erdogan-Sisi handshake and the Muslim Brotherhood

Have you seen the photograph? Turkey’s president Erdogan shaking hands with his Egyptian counterpart Abdel Fatah Al-Sisi at the World Cup in Qatar on 21 November? No, no shaking handshakes. With a wry grin, they hold hands. Look at it perceptively, please.

Erdogan who has repeatedly referred to Sisi as a murderer and a putschist… Sisi who has repeatedly accused Erdogan of attempting to destabilise his country by supporting a terrorist organization that is the Muslim Brotherhood (MB). They shook hands. Erdogan now claims that he intends to meet with al-Sisi as soon as the foreign ministers reach agreement on specific issues.

Two weeks prior to this handshake, the security teams of both countries met and agreed not to take any actions that would jeopardise their respective countries’ security. This should be interpreted as Egypt asking Turkey to reconsider its Libyan policy and Turkey asking Egypt to reconsider its position vis-a-vis the Mediterranean. According to Egyptian sources, Turkey’s only request was for Egypt to change its stance towards Turkey’s status in the eastern Mediterranean.

It is not hard to guess that the handshake was arranged ahead of time. The mediator was the Amir of Qatar, Tamim bin Hamad al Thani. His team had been going back and forth between Turkey and Egypt prior to the World Cup to make this meeting happen. This explains Amir’s cheerful and valiant expression in the background. Oh, sorry, there is also the mango incident, which appears to have prompted the reconciliation. Again, my apologies. Not mango. Mango juice. For some time, Erdogan had been serving mango juice to his visitors at the presidential palace, Beştepe. When asked about why, he claimed that mangos were sent by the Egyptian president Sisi via Turkey’s spy chief Hakan Fidan and foreign minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu, both of whom had been working on to repair relations.

Even though Egyptian presidency spokesperson Bassam Essam Rady stated on presidency’s Facebook account that the handshake would be the start of developing bilateral relations, Tariq Fahmy, a political scientist at the Cairo University, argues that there is still a long way to go and that Turkey needs to regain Egypt’s trust and that there is no agreement between two countries on thorny issues, particularly Libya and the Mediterranean.

However, the eastern Mediterranean maritime dispute and the Libyan quagmire are not the only issues causing friction between Turkey and Egypt. Interestingly, there seems to be a tacit agreement between the Turkish and Egyptian presidencies that neither side dare to bring up the ‘other issue:’ The MB. Let’s get to the heart of the issue.

The genesis of the friction

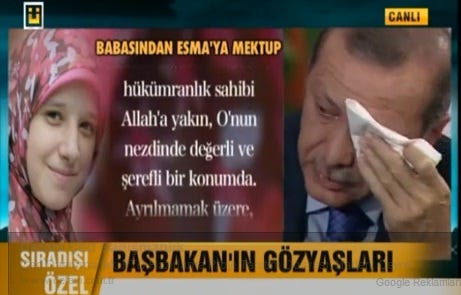

On 30 June, just as the Gezi protests were winding down in Turkey, the Morsi government was deposed and the Egyptian military took over. The MB organised large crowds to stage a sit-in in Rabia al-Adawiyya Square in Cairo. On 14 August, Egyptian security forces conducted a violent raid, killing approximately 1,400 people. Hundreds of MB leaders were arrested in the days that followed. Reports surfaced that Erdoğan had broken down in tears on hearing of the death of Esma Baltaggi, the daughter of one of the MB leaders, Mohammad Baltaggi, and on 23 August 2013 Erdoğan publicly wept while reading Mohammad Baltaggi’s letter to his deceased daughter, saying that ‘he saw his own children in this letter’.

Erdoğan’s tears and the connection he made with a young MB follower who died while taking part in protests with his children demonstrated how personally he took Morsi’s ousting. His supporters shared his sentiments.

Istanbul played a major role in preserving the spirit of the MB in the aftermath of the military coup in Egypt by hosting international conferences and meetings. Besides hosting conferences and meetings that enabled exiled MB members to connect with other Islamist groups around the world, Turkey helped the MB to remain internationally visible by enabling it to bypass the repression of Egyptian President Sisi. As Trager states, ‘From its primary base in Istanbul, [the MB] broadcasts its message through sympathetic satellite networks.’[1]

Turkey’s harbouring of MB members prompted the Egyptian regime to undertake a public relations campaign against Turkey, worsening already strained relations with regional powers such as Saudi Arabia.

Erdogan’s volte-face: Rabia sign, MBS and MBZ

We all know that Erdoğan’s actions are contingent on their utilitarian value: it is doubtful whether he would continue to condone MB’s presence in Turkey if he believed there was no benefit for him. Erdoğan’s stance on the MB began to change around 2016, which saw a period of ‘U-turns’ in Turkey’s Middle Eastern policies.

The the four-fingered Rabia symbol is a good example. The symbol initially – in the aftermath of the 2013 Egyptian coup - was used to portray Erdogan as a defender of the ousted Morsi government, a defender of ‘freedom, justice, legitimacy, and humanity as imagined under the umbrella of Islam and embedded into a bipartite worldview, with ‘the West’ in the role of antagonist’. It also implied that Erdoğan and the AKP had the ‘moral superiority and pride that stood in opposition to the oppression of Muslims around the world and the rejection of Western values’.[1]

It aimed to mobilise both domestic and international Muslim sentiment. Therefore, the Rabia icon, which immediately became Erdoğan’s ‘corporate identity’,[2] also aimed to suppress the democratic demands of those Turks who took to the streets in 2013. However, in the aftermath of the attempted coup in Turkey in July 2016 and just before the 2017 constitutional referendum, in which Turkey would become a presidential republic, Erdoğan nationalised the Rabia icon, claiming that it symbolised AKP’s worldview: one nation, one motherland, one flag, one state. A brand-new meaning was given to the sign, separating it from its origins.

Apart from Turkey’s support for the MB and Saudi Arabia’s support for Egypt’s coup, relations between the two countries ground to a halt, both economically and diplomatically, following the murder of Saudi dissident journalist Jamal Khashoggi in Saudi Arabia’s consulate in Istanbul in 2018. According to both Turkish and US intelligence, the brutal killing had been ordered by the crown prince and de facto ruler, Muhammad Bin Salman (MBS), and carried out by a team including one of his close aides. Erdoğan piled international pressure on MBS while revealing audio recordings of the killing. As a result, relations between Turkey and Saudi Arabia further deteriorated, leading to an unofficial Saudi boycott of Turkish exports. Whereas the two countries’ foreign trade volume had been 5.2 billion USD in 2015, it was reduced to 3.3 billion by 2019.

Following media outrage over Khashoggi’s murder, MBS withdrew from the limelight and did not travel outside Saudi Arabia or give interviews to non-Saudi media networks until March 2022. In an interview published in the American journal The Atlantic, MBS claimed that ‘the Khashoggi incident was the worst thing ever to happen to [him], because it could have ruined all of [his] plans to reform the country’. He also stated that he had been ‘hurt a lot’. A month after this interview, Turkey abruptly handed over the Khashoggi trial to Saudi Arabia, claiming that as the Saudis had refused to extradite the suspects, the Turkish courts could do little in the absence of defendants. However, in 2018, at a conference organised by an NGO called the ‘League of Parliamentarians for Al-Quds’ in Istanbul, Erdoğan claimed that the voice recordings pertaining to the Khashoggi murder proved that it was premeditated and had warned that, if Saudi Arabia did not prosecute the case properly, the Istanbul courts would do so in accordance with international law because the incident had occurred on Turkish soil. ‘They [the Saudis] think we are stupid, they think the world is stupid,’ Erdoğan continued. However, the Erdoğan of 2022 thought differently from the Erdoğan of 2018. What was behind this volte-face was clear to many: a month following his visit to Jeddah, Erdoğan invited MBS to Turkey, hoping these visits would lead to a ‘major boost to bilateral ties as well as Turkey’s deteriorating economy’.

A similar conciliation process was initiated with the UAE. Between November 2021 and May 2022, UAE President Mohammad bin Zayed (MBZ) and Erdoğan visited each other’s nations on several occasions. Those visits occurred after a nine-year period of tense relations, which began with Turkey’s support of the MB – a period in which numerous AKP officials and ministers, including the minister of foreign affairs and minister of the interior, accused MBZ of having financed the attempted coup in Turkey on 15 July 2016.

Sisi, who saved Egypt from the MB

Turkey, unsurprisingly, also has been seeking to improve relations with Egypt; the deputy foreign ministers have met several times and Turkey’s Foreign Minister, Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu, has indicated repeatedly that Turkey is determined to improve relations. However, a rapprochement with President Sisi of Egypt seems to be harder than one with MBS or MBZ, as Sisi in his rhetoric still portrays the MB as the villain and himself as having saved the country from that malicious organisation. The media, also controlled by the Egyptian state, seem to be following the same rhetoric. The third season of a popular television series in Egypt called Al- Ikhtiar (The Choice), which depicts the MB’s short rule and ousting, has become one of the most-watched series in Egypt. In a trailer, ‘the show promises to take viewers behind the scenes of Egypt’s most dangerous 96 hours, further claiming that the series will demonstrate Sisi’s determination to save Egypt from the Muslim Brotherhood’s dark path.’

AKP’s conspicuous attempts to repair the damage caused by its support for the Islamist movements after the uprisings raise the obvious question: Will the AKP government extradite MB members who live in Turkey?

A senior but former MB member to whom I put this question told me that ‘Erdoğan is pragmatic and does whatever he thinks is necessary for his country, such as making peace with Saudi Arabia, but he will not extradite the MB members because many of them are now Turkish citizens.’ A few weeks after I conducted these interviews, at the end of April 2022, one of the primary MB television channels, Mekameleen, ceased broadcasting. Al Sharq TV, owned by AymanNour, followed suit and stopped broadcasting in Turkey. In a written statement, the management of Mekameleen statedthat ‘it has decided to move the broadcast, studios, and all activities of the channel outside of Turkey, owing to the conditions that are not hidden from anyone and with the concern of continuing the mission of the channel to convey the whole truth. Our broadcasts from different parts of the world will be restarted.’

The Muslim Brotherhood seems to be unshocked by Erdogan’s U-turns and capitulations, owing to their familiarity with the pulls and pushes of authoritarian regimes. ‘It was bound to happen’ they say. ‘Classic Erdogan’, they add. Another reason for this defeatism is that the MB is going through its deepest crisis since its foundation in 1928. Not only are the majority of its leaders and members imprisoned in Egypt, but those in exile have also fallen into disarray. The major schism is between the leaders in London and Istanbul, with each one claiming authority over the other and neither having a clear vision for the future of the movement.

Meanwhile, Turkish Islamists expressing their disappointment, - albeit sotto voce. One of them states that he ‘cannot acquiesce Erdogan’s handshake with the murderer Sisi. No and never! I despise Sisi and everything he stands for. I fully identify with Morsi and the values he represents. I feel very sad and wounded.’ Another says he was devastated after seeing the photo of the handshake: ‘I was devastated on behalf of the Muslim world.’

Apparently, there appears to be a lot that Turkish Islamists could learn from their older Brothers. Ironically, the MB had been attempting to learn from their Turkish counterparts in the aftermath of the Egyptian revolution in 2011. But that is a subject for another newsletter.

[1] Pierre Hecker, ‘The ‘Arab Spring’ and the End of Turkish Democracy,’ in Arab Spring: modernity, identity and change, ed. Eid Mohamed and Dalia Fahmy (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), 69.

[2] Hecker, ‘The ‘Arab Spring’, 71.

[1] Eric Trager Arab fall, 233.